No Coming Home

An incarcerated woman’s hopes of obtaining freedom vanished after Pa.’s powerful pardon board took an unprecedented second vote.

Gail Stallworth was trying to win the lottery.

At least, that’s what it felt like.

In half a century, only 17 of the hundreds of women serving life sentences in Pennsylvania have been offered a second chance at freedom. In 2019, Stallworth began her attempt to become one of them.

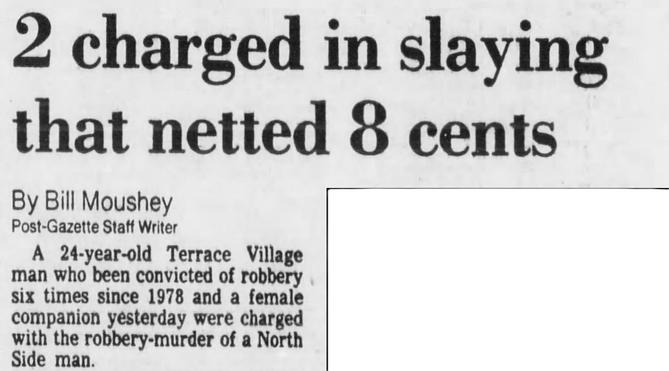

Stallworth, now 64, took a life when she was 25 years old. She shot and killed a man named Donald Stoker during a botched robbery that netted her and her accomplice eight cents. She never shied away from the fact she did something that, to many, is unforgivable.

But the Pennsylvania Constitution recognizes that people change, and provides a process for the governor to grant commutation, which reduces or ends a prison sentence.

For Pennsylvania’s population of people serving life sentences, the third largest in the country, commutation is one of the only avenues to freedom, albeit a slim one. Between 1999 and 2018, governors granted just 10 life commutations.

But Stallworth applied in 2019. That year former Gov. Tom Wolf granted 19 life commutations, more than in the prior 20 years combined. An official from the Board of Pardons, the powerful state body that reviews and recommends clemency applications to the governor, visited Stallworth’s prison and encouraged her to apply.

The board believes in second chances, Stallworth remembers him telling the women incarcerated at SCI Muncy.

“I believed him,” Stallworth said.

Stallworth knew her odds were low. The commutation process is notoriously arduous and opaque. It can take years for an application to reach the board, and then all five members must agree to send it on to the governor.

Stallworth still couldn’t have predicted what would happen to her application. That’s because it has likely never happened in the board’s history, experts told Spotlight PA.

Her application made it to the board. It garnered all five votes to reach Gov. Josh Shapiro for his final approval, power the constitution gives the governor alone.

But the decision wouldn’t fall to Shapiro.

Instead, the board took an unprecedented step.

They voted again, rejecting Stallworth’s plea. Her winning ticket was gone.

A second chance

To make her case before the board, Gail Stallworth gathered evidence of a changed life: the humanitarian award she received for saving a corrections officer who was choking on candy; certificates for self-help training, vocational programs, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation; and the recommendation from prison officials who, after overseeing her incarceration for more than 30 years, agreed she deserved a second chance.

In August 2022, the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, a body of five elected officials and political appointees, reviewed her application and decided they needed more time to make a decision.

An agonizing 14 months passed. And then, on Oct. 13, 2023, the day arrived.

Lt. Gov. Austin Davis called Stallworth’s name. Board Secretary Shelley Watson noted no opposition to Stallworth’s release.

The board discussed minor behavioral infractions Stallworth earned in the 1990s for contraband: dining hall food she shouldn’t have taken back to her cell and a money order an acquaintance sent her.

In interviews, Stallworth was nervous and misremembered some details, but always took ownership of her fatal actions.

“It seems that she's never denied, number one, that when she went to that house, it was for something that wasn't good,” then-Attorney General Michelle Henry said at the meeting. Henry served on the board at that time.

“Whether it was to rob for drugs, or just take money, she's always maintained that there was something that was going to happen at that house that wasn't good and that she was the shooter.”

At the end of the meeting, the board read out their votes.

Marsha Grayson, victim advocate? Yes.

John Williams, psychiatrist? Yes.

Harris Gubernick, corrections expert? Yes.

Attorney General Henry? Yes.

Lt. Gov. Davis? Yes.

Five yeses, the difficult-to-reach unanimous consent required by the Pennsylvania Constitution for a recommendation to the governor.

“I felt excited, overjoyed, as well as humble and grateful to know that I was recommended for commutation,” Stallworth told Spotlight PA.

It was a surreal moment, she said.

Stallworth began preparing to reenter society for the first time in more than three decades. She shipped books and photos to friends who were waiting for her on the outside. She gave other possessions away to friends who would need them on the inside.

A month passed. Then, two.

Shapiro signed commutations for men who the board recommended in October alongside Stallworth, and they went home.

But Stallworth’s application sat.

Lacking transparency

The board doesn't provide explanations for its decisions. There are no written benchmarks a person can use to understand whether they might be a good candidate, an opacity that Stallworth’s attorney Sabirha Williams knows firsthand.

Williams, an attorney for the Amistad Law Project, has been shepherding clients serving life sentences through the commutation process since 2021, and it never ceases to frustrate her.

The morning of May 16, 2024, she drove from her office in Philadelphia to SCI Camp Hill, a prison where three of her incarcerated clients were scheduled to sit for interviews with the Board of Pardons.

The board was holding a public hearing the next day, and Williams’ clients would be up for consideration.

In the final year of Gov. Tom Wolf’s administration, the board unveiled a plan to digitize the pardons and commutations process by the beginning of 2023.

But the effort was harder than initially expected. For now, candidates make their case on paper, a lengthy process for both the applicants and the staff that handles the files and answers their questions via phone or email.

By the time Williams gets involved, her clients have typically done years of legwork to get their application past the “merit review” stage, when the board decides whether someone will advance to a public hearing.

To prepare for the board interview, Williams meets with clients two or three times a week.

She helps them go over the parts of their life that, in Williams’ experience, the board finds important for applicants for commutation: their childhood, their crime, and their remorse.

Williams, who experienced violent crime growing up in Philadelphia, takes the position of the victim’s family during these sessions to help her clients find the words she would want to hear.

She doesn’t spend a lot of time on change. While her clients have accomplishments they’re proud of, in Williams’ experience, the board rarely asks those types of questions.

“You would think rehabilitation would be a focus for this kind of process,” she said, “but what I’ve seen is that it’s not really.”

During the board interview, she sits in the room, but due to fear of hurting their case, she doesn’t intervene when a client fumbles or misremembers.

And when they want to know why their application had full support at the merit review stage but garnered zero votes at the public hearing, she can’t tell them. There are no rules or laws requiring the board to explain itself to applicants, to the public, or to advocates like Williams.

But Williams has had some success too.

Stallworth had received the full board’s support six months prior. She was still incarcerated, but it was just a matter of time, Williams thought. Everyone in Stallworth’s corner — her attorney, her friends in prison, the lifelong friend she considered family waiting for her — was confident Shapiro would see the same changed person as the board and send Stallworth home.

So when Williams walked into the prison that day, Stallworth wasn’t her focus.

She hadn’t seen the email.

Watson, the board secretary, approached her.

“I’m sorry about Gail.”

A changed process

While clemency has existed in Pennsylvania since the state was a colony, the process Stallworth navigated has been in place only since 1997.

The Board of Pardons was introduced in 1872, and for decades scores of people received commutation every year. Governors shortened prison sentences for robberies, murders, or the odd political corruption case.

The process went largely unchanged for more than a century.

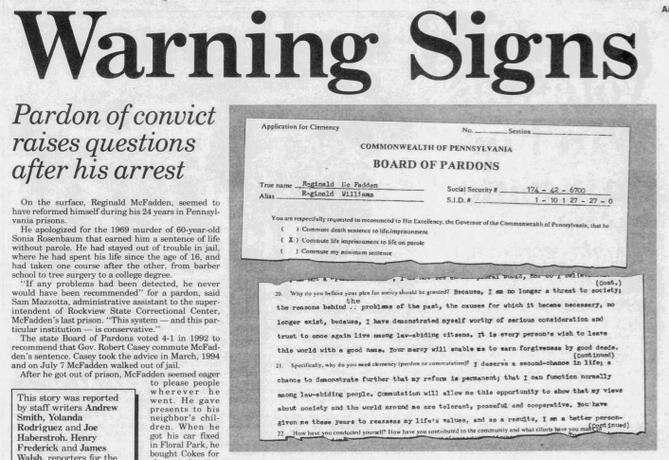

And then in 1994, Gov. Robert Casey Sr. commuted the sentence of Reginald McFadden, an event that would reduce the chance of commutation for people serving life sentences, like Stallworth, to nearly nothing.

When he was 16 years old, McFadden and three other teenagers killed Sonia Rosenbaum, a 66-year-old woman living in West Philadelphia. They broke into Rosenbaum’s home, bound her, and left her to suffocate after stealing $20.

When McFadden was 39, he submitted his eighth application for commutation to the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons. He’d secured the board’s recommendation three times before, but Govs. Milton Shapp and Dick Thornburgh ultimately declined to commute his sentence.

This time, though, he had the support of the prison that held him. While today’s applicants go through extensive interviews with the board members, in 1992 the board voted 4-1 to recommend McFadden without ever meeting him.

Casey, heeding their recommendation more than a year later, commuted McFadden in 1994.

But the year McFadden’s application sat on Casey’s desk led to procedural mishaps, and by the time he signed it, parole officials incorrectly released McFadden straight to the public instead of into a two-year work release program.

McFadden killed two people in the 92 days he was free — Margaret Kierer and Robert Silk — and is suspected of killing a third, Dana Blaise DeMarco. He also abducted and raped another woman, Jeremy Brown.

Reoffense is rare among those who receive commutation for life sentences, a population that is often advanced in age and decades removed from their crime. But McFadden was just 41, having served less than 25 years of his life sentence before the board recommended commutation.

His recommendation from the prison came after he informed on fellow incarcerated individuals during the SCI Camp Hill riot in 1989. The board didn’t know that among his peers McFadden was disliked and mistrusted.

In retrospect, officials acknowledged that procedural failures, miscommunications, and shoddy vetting allowed McFadden to walk free.

The fallout from his commutation had drastic and lasting consequences on the process.

Lt. Gov. Mark Singel, until then considered Casey’s natural successor, lost the 1994 gubernatorial election to little-known challenger Tom Ridge, who seized on Singel’s support for McFadden in a series of campaign advertisements.

On his first day in office, Ridge called a special session of the General Assembly that led to a constitutional change to require unanimous consent for the board to recommend a commutation of life to the governor.

In the two decades before McFadden’s release, governors granted 285 commutations. In the two decades after, governors granted six.

The session also created the Office of Victim Advocate (OVA), placed a victim advocate on the board, and opened deliberations for the first time to input from the people whose lives were forever changed by the crimes of those applying for mercy.

In the decades since, the family members and friends of murder victims have spoken both in favor and in opposition to commutation for the people who killed their loved ones. Testimony in support of an application does not always result in a recommendation, experts told Spotlight PA; testimony against an application almost always dooms it.

Too late

When Grace Schriner discovered her nephew’s killer was being considered for commutation, it was already too late. It was Dec. 14, 2023, two months after the board had already put their rare unanimous support behind Gail Stallworth.

Schriner remembers her nephew Donald as troubled, but harmless.

After he developed a drug problem, he became zombie-like, almost catatonic in her memory, but never violent. Before his addiction, he had an amazing talent for art. He was self-taught and could draw anything.

He could have produced so much beauty in the world, Schriner told the Pennsylvania Office of Victim Advocate. But because of Stallworth, he wasn’t able to.

How Schriner’s perspective came to the board was unheard of, according to experts who spoke to Spotlight PA.

In 2021, Pennsylvania enacted a law codifying rules around how victims participate in the clemency process.

Once an applicant’s public hearing is set, the OVA and the board must make every effort to reach such victims and determine whether they’d like to provide input.

They must do so at least 60 days before the hearing is set to happen, and the OVA must chronicle attempts to reach victims in a report to board members. If the board fails to follow the law, any resulting vote is nullified.

If staff takes these steps and doesn’t hear from a victim in time, any subsequent testimony should be sent to the governor as an addendum to the recommendation, said Brandon Flood, who served as the board secretary from 2019 to 2021.

“Once the board makes the recommendation to the governor on the application,” Flood said, “at that point, it’s in the governor’s hands.”

But the regulations governing the board are old and ambiguous, he said, allowing politics and the personal preferences of board members to interfere with the process.

The OVA tried to reach Donald Stoker’s family when Stallworth’s application was first up for consideration in 2022. The office was not aware of any opposition when the vote first occurred in 2023, according to Suzanne Estrella, the state’s victim advocate.

It is unclear who the OVA tried to reach during this first attempt. But after the vote, the board did something unprecedented. They directed the OVA to try again.

“After the Board of Pardons vote on Ms. Stallworth’s application in October 2023, the Board of Pardons asked OVA to attempt again to contact the victim’s family,” Estrella wrote in response to questions from Spotlight PA. “December 14, 2023 was the first time OVA contacted Ms. Schriner.”

Schriner panicked in response. She was ready to get on a plane, to go anywhere, to do anything, to stop Stallworth’s commutation. In her conversation with the OVA, she pleaded with Gov. Josh Shapiro to disregard the board’s recommendation and deny Stallworth’s application.

Spotlight PA asked Shapiro’s office if the governor was involved in the decision to continue investigating Stallworth’s case, but the office did not answer the question. Instead, Shapiro spokesperson Manuel Bonder sent the following statement: “Governor Shapiro evaluates every pardon and commutation case individually based on its circumstances, which are often complex, and on its merits.

“The Governor believes input from victims’ families and loved ones is a crucial factor that must be taken into account when making decisions about pardons and commutations.”

A homecoming undone

Cornelius Harp, Neil to his friends, answered the phone on May 17.

“This is a call from an incarcerated individual at SCI Muncy,” a familiar robotic voice told him. It was Gail. Her voice was shaking.

Harp and Stallworth had been friends since they were children. They attended the same church in Pittsburgh. Stallworth’s parents died when she was young, so she became part of Harp’s family, more like a sister than a friend.

He’d been preparing for her homecoming for months. He received the things she sent to his house in North Carolina. He bought her a car. He’d involved his church, his family, in the preparations.

His niece was so excited to teach Aunt Gail how to use a phone.

So when Stallworth told him there was a revote, that she wasn’t coming home, he didn’t understand.

The Office of Victim Advocate had known about Schriner’s opposition in December, five months prior, but Stallworth and her supporters didn’t find out her case had been reopened until the morning of the vote.

Stallworth watched the meeting from the office of Muncy Superintendent Wendy Nicholas, who had also been surprised by the news of a new hearing.

The board members appeared in their Zoom boxes and began moving through the agenda. The board addressed other candidates seeking a second chance, granted some, denied others, and then finally reached old business.

“Gail Stallworth was heard by the board at the Oct. 13, 2023 session and was recommended to the Governor,” began Lt. Gov. Davis. “After the vote, it came to light that there was input from a member of the victim's family which should have been available to the board prior to the vote.

“Accordingly, I directed that the record be reopened to allow the board to consider the application with the full, required information, and not as a reflection of the merits of the case.”

Watson read Schriner’s statements to the board, and called the vote.

“Mrs. Grayson?”

“Yes.”

“Dr. Williams?”

“No.”

“Mr. Gubernick?”

“No.”

“General Henry?”

“Yes.”

“Gov. Davis?”

“Yes.”

“Application denied.”

Gail Stallworth is still incarcerated at SCI Muncy. The future of her freedom is unclear.

Sabirha Williams is exploring avenues to seek justice for Stallworth, who she believes has been wronged by an unfair process.

Grace Schriner did not respond to letters mailed and phone calls made to publicly available contact information.

The Office of Victim Advocate told Spotlight PA it is working with the Board of Pardons to improve communication about its attempts to reach victims.

The Board of Pardons declined Spotlight PA requests for interviews with Lt. Gov. Austin Davis and Board Secretary Shelley Watson. When asked whether there is precedent for redoing a final commutation vote, spokesperson Kirstin Alvanitakis did not respond.

Neil Harp is still waiting for Stallworth to come home. The room he prepared for his friend remains empty.

How We Reported This Story

To understand Pennsylvania’s commutation process and what happened to Gail Stallworth’s application, Spotlight PA analyzed the public data on commutations provided by the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, as well as data compiled by Elaine Selan with the PA Commutation Work Group, a group of volunteers that monitor Board of Pardons public hearings and merit reviews.

Spotlight PA interviewed Gail Stallworth via phone and email, and spoke with her attorney Sabirha Williams and other advocates for both applicants and victims who are familiar with the commutations process.

Descriptions of changes at the Board of Pardons following the case of Reginald McFadden and the downstream effects of his commutation relied heavily on two sources: “The Saga of Reginald McFadden — ‘Pennsylvania’s Willie Horton’ and the Commutation of Life Sentences in the Commonwealth” by Regina Austin; and “A Life Sentence” by Samantha Broun.

Multiple attempts to reach Grace Schriner and other members of Donald Stoker’s family, including phone calls and mailed letters, were not successful. Statements and feelings attributed to Schriner come from the statement she gave to the Pennsylvania Office of Victim Advocate, which was read aloud at the May 17, 2024 hearing before the board revoted on Stallworth’s case.

The newsroom requested interviews with Board Secretary Shelley Watson and Lt. Gov. Austin Davis, who serves as chair and leader of the Board. These requests were denied. In lieu of an interview, Spotlight PA sent several rounds of questions to Davis spokesperson Kirstin Alvanitakis. Read those questions and responses here.

Gov. Josh Shapiro’s office also did not respond to direct questions. Read those questions and responses here.

Victim Advocate Suzanne Estrella and Department of Corrections spokesperson Maria Bivens answered questions about the case via email.

Spotlight PA reached out to Board of Pardons members Harris Gubernick, John Williams, and Marsha Grayson. All three did not respond.