Financial Delayed

School administrators struggled to use an unfamiliar and glitchy system that exacerbated financial aid delays for thousands of college students.

By October, the scale of the crisis was clear.

State grants that thousands of students were counting on to pay for college were weeks behind schedule. The botched rollout of a new federal financial aid form had already caused serious delays. Then, the new software system the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA) was using to run the grant program slowed things down even more.

“I am just sick over the situation we are in with the new system,” Elizabeth McCloud, a top official at PHEAA, emailed a colleague on Oct. 13. The upgrades were intended to make running the program more efficient. But the feedback was clear, McCloud wrote: the new software was “falling short.”

The PA State Grant Program is the commonwealth’s largest need-based financial aid program, giving more than 100,000 students an average of $2,000 each semester. PHEAA relies on data from the federal government to determine which students are eligible.

A Spotlight PA investigation based on more than two dozen interviews and hundreds of pages of emails obtained through public records requests provides a behind-the-scenes look at how the program was thrown into turmoil last year.

PHEAA’s decision to forge ahead with a new and unproven system while grappling with unprecedented federal delays proved to be a critical mistake. As a result, students were left waiting months longer than usual for urgently-needed aid. Students told Spotlight PA they took out loans, spent down their savings, and scrimped on bills to make up the shortfall.

As the problems piled up, PHEAA struggled to communicate with students and schools about the delays. Meanwhile, financial aid administrators grappled with an unfamiliar system that was riddled with glitches, some of which still had not been resolved by March.

Ahead of releasing the new software, PHEAA said it would be streamlined and user-friendly, “to get what you need faster.” But when it launched, it was slow to load and difficult to use, school administrators said. Many student records were missing crucial information. Updates submitted to PHEAA could take weeks to process.

Four financial aid administrators told Spotlight PA they could not think of anything about the new system that was better than the old one.

“It’s still hard to navigate even now,” Christy Snedeker, director of undergraduate financial aid at Wilkes University, said in March. “It’s just not very informative of a system at all.”

School administrators questioned why PHEAA pressed ahead with its software upgrades during what was already an unusually turbulent year in the world of college financial aid.

PHEAA officials said there was no way the agency could have anticipated the extent of the disruption caused by the changes to the federal form that acts as the backbone of the financial aid system nationwide.

By the time this was clear, it was too late to return the whole program to the old system, which would have taken months of work, said Nathan Hench, PHEAA’s senior vice president for public affairs. Instead, the agency used both the old and new systems, moving data back and forth between them, which eased some difficulties while creating others.

In February, PHEAA announced that it would run the program off the old system in the coming academic year, before relaunching the new one in 2026.

“We just can’t have another year like ‘24-25,” Hench said.

In a normal year, students receive grant funds for the fall semester by early September. This year, some were still waiting as late as the end of March. Some grants for the spring semester were also delayed.

“I just don’t understand how badly a system has to be designed for them to take this long,” said Nicole Etolen, whose son was still waiting on more than $1,500 in aid for the fall semester more than three months after it ended.

“You’re tired of PHEAA, we’re tired of PHEAA, it’s going around,” a financial aid counselor at Northampton Community College told Etolen’s son in an email earlier this year. “Sadly, no updates.”

‘The snowball just kept getting bigger’

PHEAA officials knew for several years that the agency’s largest program would face two major changes in 2024.

In early 2022, PHEAA began to explore the possibility of upgrading the software used to manage the PA State Grant Program. The one in use at the time was so old that no one in the agency could pinpoint exactly when it was created. It ran on a mainframe that was expensive to maintain, and was written using COBOL, a 65-year-old programming language that few developers still learn.

The U.S. Department of Education was making even bigger changes. Students and their families had complained for years that the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, known as FAFSA, was too long and too complicated. In late 2020, President Donald Trump signed a bill into law ordering the department to simplify the application form.

In early 2022, the federal government pushed the launch of the redesigned FAFSA back a year, to 2024 — the same year PHEAA planned to roll out its new system, called GrantUs.

The agency relies on FAFSA data to determine which students qualify for state grants. But at first, PHEAA had no reason to be overly alarmed that the federal overhaul and the launch of GrantUs would overlap, Hench told Spotlight PA.

“I don’t know if the concern was, like, code red or anything, at that point in time,” he said.

In hindsight, however, the timing was a recipe for disaster.

In a late October speech, PHEAA CEO James Steeley recalled the agency’s predicament ahead of launching the new system.

“It started out,” he said at a financial aid conference, “like a small snowball” – the new FAFSA wasn’t ready until December 2023, three months later than usual.

“But then the snowball started rolling downhill.”

PHEAA didn’t receive student records from the federal government until mid-April 2024.

“The snowball just kept getting bigger.”

Those records were full of errors. Eventually, the federal education department agreed to reprocess them.

“Now the snowball was getting really large.”

PHEAA didn’t ultimately receive usable files until the second half of May 2024 — eight months later than usual.

And that was just the beginning of the setbacks.

The agency typically receives the federal data in a steady stream over the course of more than half a year. Instead, it was inundated with more than half a million records in one go. GrantUs was not built to handle so much data all at once. And even after PHEAA received the updated records, some of them required further corrections by the federal government, Hench said.

By the time PHEAA realized the extent of the issues the FAFSA data would cause for GrantUs, it was too late to reprogram the mainframe and return entirely to the old system, he said.

In June, PHEAA sent colleges and universities a backout schedule that accounted for the delays. But the agency soon began to fall behind, even as staff worked frantically to move things forward, records show.

“Between you and me, this is not going well,” McCloud, the PHEAA official in charge of the state grant program, wrote in an email to a colleague in July. The agency’s vice president overseeing the system upgrades, she wrote, “doesn’t seem ready to face up to just how bad of a situation we are in with the project.”

The snowball had become an avalanche.

‘Is this a system lag or what?’

To establish which students qualify for the grants, PHEAA depends on updates submitted by financial aid officials at colleges and universities, in addition to FAFSA data.

But in October, when school administrators tried to use the new system, they ran into one mishap after another. And inside PHEAA, frustration over the IT issues was mounting.

“Like, is this a system lag or what?” one agency staffer asked colleagues, frustrated that a change to a student’s file submitted by a community college had taken more than two weeks to appear.

“I feel like I’m running in circles trying to constantly fix things and make changes just for records to sit and nothing happen,” she vented.

“I can’t even figure out how to determine if a record went through screening and when.”

The tech troubles fell into two categories, according to a summary of feedback from PHEAA employees that was shared with agency management. Some functions the agency had requested from the contractor hired to build GrantUs didn’t work, or had been missed. Others couldn’t be turned on because the influx of records from the federal government had bogged the software down, making it very slow to load.

In the fall, it could take as long as two minutes to pull up a student’s file, financial aid staff told Spotlight PA. As they worked through hundreds, or thousands, of student records, those minutes added up. The lags made it hard to tell whether the system was still processing, or had timed out. One financial aid administrator complained to PHEAA in October that he seemed to be spending longer waiting for GrantUs to load the next page, or process his changes, than actually updating student records.

The feedback document laid out a long list of tech problems: records were being processed using “unvetted data”; vital information was missing from student files; processing issues made it impossible to know whether applications had been screened properly. The system “just cannot handle the amount of data that needs to be evaluated” and some workarounds were causing “data inconsistencies” and “misunderstanding,” the document said.

To deal with the software lags, PHEAA officials decided over the summer to use the old mainframe for some crucial functions. But since the two systems were not designed to be connected, this caused problems of its own. The agency had to transfer data from GrantUs to its predecessor, run calculations, then send it back again — a process that could take days.

The tech difficulties rippled outward to the schools and students that relied on PHEAA. Changes that schools needed to submit before students could get the grant money sometimes took weeks, or even months, for PHEAA to process. Some students had their applications rejected in error; others were told incorrectly that they qualified.

The contractor hired to develop GrantUs referred questions from Spotlight PA about the software glitches to PHEAA. Bethany Coleman, a PHEAA spokesperson, declined to respond to specific questions about the tech issues raised in the document.

“There has been a complete lack of communication on the project as a whole,” the document concluded.

“This has been a barrier in staff being able to do their jobs at the most efficient level possible.”

“The timeline keeps moving”

PHEAA employees weren’t the only ones who complained about a lack of communication.

As one setback bled into the next, the agency repeatedly underestimated how long things would take to fix. Officials initially said they would have student records loaded into GrantUs by early July, but still hadn’t finished by the end of that month. Then, information that PHEAA told schools to expect in September didn’t arrive until October, and was incomplete.

“Schools are communicating with students and parents as best they can but they honestly don’t know what is really happening,” the Pennsylvania Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators told the state education department, according to a summary of the conversation that was shared with the deputy secretary for higher education in October. “They keep being told one thing and the timeline keeps moving.”

An advisory committee of school representatives was not consulted about the rollout of GrantUs, the notes say. There was “no in-depth training” on how to use the new system; as a result, school administrators “don’t even know what they’re looking at,” according to the summary.

Coleman, the PHEAA spokesperson, said in a statement that the agency has “strived to keep open lines of communication with PASFAA and all our school partners, with whom we have strong working relationships.”

Some school administrators said PHEAA responded promptly when they raised issues. Still, complaints about a lack of communication persisted over the fall semester, records show.

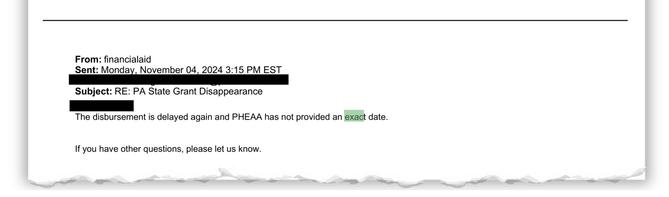

“The disbursement is delayed again and PHEAA has not provided an exact date,” the financial aid office at Pennsylvania Western University told a student on Nov. 4.

“We have had absolutely no update on funds from them,” a financial aid counselor at Commonwealth University emailed a student on Nov. 13. “We ask, they say they aren’t sure.”

Students struggled to get answers from PHEAA too.

Messages sent in the agency’s online portal could go unanswered for weeks. When students called PHEAA, they often could not get through.

“Trying to contact them is a nightmare,” said Kaitlin Barnes, a student at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. By the end of March, she was still waiting on money for the spring semester that typically arrives in late January. When Barnes called PHEAA to ask about the delay, it took 15 tries and more than an hour to get through, she said.

There was also no guarantee that information provided by PHEAA’s call center would be accurate.

Students who managed to speak with a PHEAA representative were “often given wrong or bad information until we intervene (we’ve witnessed this when they’ve called PHEAA from our office),” Tiffany Potts, the financial aid director at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, told colleagues in a November email.

Many colleges and universities tried to shield students from the financial blow of the delays by waiving late fees, crediting their accounts with estimated grant amounts, and relaxing policies that typically prevent those with outstanding balances from registering for classes. Still, there was less that schools could do for students who needed the grant money to pay rent, or buy groceries and gas.

As February turned to March, Tiffany O’Brien was still waiting on almost $2,450 in aid for the fall semester. O’Brien, who is enrolled in a surgical technology program at Carlow University in Pittsburgh, said the delay forced her to use up her savings. By January, she said, her bank account was down to $92.

“I feel like this grant money is designed to prevent me from being in this position, and now I’m here,” she said.

O’Brien finally received the money in March.

“All I could do is cry”

By late November, PHEAA had sent about 80% of the grant money to colleges and universities, records show. The work of ensuring that all eligible students received their grants, however, was far from over.

After an error wrongly flagged many students as ineligible, it took PHEAA months to clean up the mistakes. Other applications were flagged as incomplete, school officials said, even though students were never told they needed to provide additional information, or weren’t told what was missing.

As the calendar turned to 2025 and the spring semester got underway, some schools began having weekly meetings with PHEAA, going through student accounts one by one to resolve whether those still waiting should qualify.

“We’re making progress, but it’s a pretty laborious process,” Alyssa Dobson, the financial aid director at Slippery Rock University, said in early March.

Even when the problem is clear, fixing it can still take months.

Monjeana Henderson knew the wrong school was listed on her account. Henderson, a student at Penn State’s Greater Allegheny campus, said the financial aid office asked PHEAA in December to correct that. In early February, the agency told her the update had been processed: “They have you in queue to rerun your eligibility ASAP.”

As a full-time student and mother of three, Henderson’s budget was already tight. Without the grant money, she relied on ‘buy now, pay later’ services, ran up her credit card bill, and drove to and from campus with an expired inspection sticker on her car.

By late February, Henderson’s account showed she had been approved for around $2,600 for the fall semester. But when she checked again, a few weeks later, her grants for both the fall and spring semesters had been canceled.

When she saw the message, her heart sank, she told Spotlight PA. Her credit card debt was piling up.

“All I could do is cry.”

Then, later in the month, Henderson finally received the money for both semesters.

The problem, PHEAA told her, was a glitch in the system.